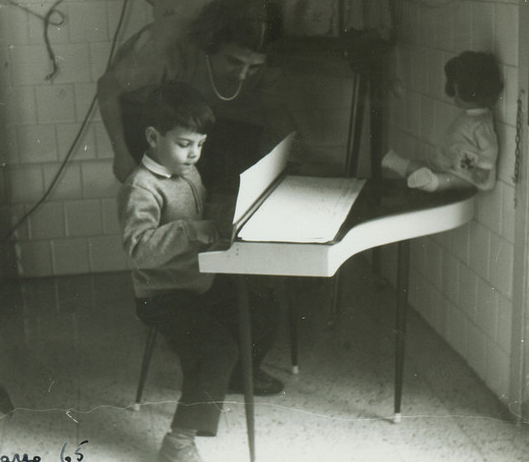

Photo by Cosciansky, used under Creative Commons licence

Photo by Cosciansky, used under Creative Commons licence

The Matchmaker of Hendon

My mother was a spinner of tales both tall and long. There was the story of the Tailor’s Tallit, which proves that a garment can be too much admired, the legend of the Bencher of Babylon, whose words may be read, but never spoken, and the tale of the Herring Bride and what became of her one true love. But these stories were not her best. She told her best story only twice: once to me, when I was a child and once to my own children, six months before she died. It was the tale of the Matchmaker of Hendon, the finest matchmaker in the world.

Matchmakers, my mother told the children, used to be more plentiful than they are now. It was, she sighed, a time when concern for one’s place in heaven was greater than today. For do we not learn that one who makes three successful matches guarantees thereby her seat in the world to come? Yes, there were matchmakers for the religious and the not-so-religious, for the Zionist and the Chareidi, for the Liberal, the Progressive, the Satmar and the Gerer. Not like today. In those days, to be the best matchmaker in the world, you really had to be something. You’d think, then, that the Matchmaker of Hendon was maybe raised and schooled in the art? That she trained with the great matchmakers of Paris, Jerusalem and New York? Not so. In fact, for many years she taught the piano to children.

“Like Zeida?” my children interrupted.

“Yes,” replied my mother, “like your grandfather, the Matchmaker of Hendon was a piano teacher. Now, do you want to tell the story or shall I?”

Day by day, young people passed through the Matchmaker’s home, sullen or studious, reluctant or eager. She saw that her role was not simply to teach these youths to strike the keys, but also to find the music which was most suited to them. And as her pupils grew to adulthood, she began to see patterns not only within each student but also between them. She made her first match between two of her students, then between a student and a friend’s child. As time went on, she began to discern suitable matches between people she had merely glanced, or spoken with for a few moments. It became obvious that she possessed a gift.

The Matchmaker of Hendon, we may note in passing, was herself unmarried. She came to feel that this gave her an ‘ear’ for matchmaking, just as one can more truly appreciate music if one is not humming a contrary tune. And so, over time, she came to be known as a talented matchmaker.

***

My mother paused.

“So far,” she said, “so what?”

My children blinked.

“Yes,” she said, “so what? So she’d made a few matches. No big deal.” She waved her hand airily. “Who hasn’t made a few matches? That just made her a matchmaker. Not the finest in the world. No, it took something else to win her that title. But eh, I don’t know if you’re really interested in this story. Maybe you’re tired?”

Once the clamour died down, my mother continued.

The Matchmaker of Hendon’s most celebrated case concerned the son of a certain Rabbi. This young man was bright, pleasant, learned in Torah, gentle of heart and neatly-trimmed of beard: all that a bride could wish. But he was marred by a peculiar affliction. He perspired. All men perspire, of course, but this youth was exceptional. In general not inclined to sweat, when he became interested by a young woman moisture poured from him, and with it a pungent and unappealing smell. The more attracted he was, the more foul the scent. The odour, which was equally uncontrollable by lotion, cream or pill, was enough to deter any woman. In desperation, he sought out Matchmaker of Hendon and pleaded for her aid. After he left her, she sat, as was her habit, in a chair overlooking the window, stirring her tea very slowly, sipping with very small sips, and thinking very deeply indeed. At last, decisive, she drank the tea to its dregs, stood up and made a single telephone call.

Three months later, the malodorous young man was married. At the wedding, the guests naturally declared that the groom was wise and learned, and the bride beautiful and virtuous but, in truth, only the virtue and wisdom of the Matchmaker were fully discussed. The bride was attractive, kind and gentle, marred by only one tiny flaw. As a child, she had fallen from a swing onto her nose. Its appearance was not damaged, but the blow had deprived her forever of a sense of smell. All odours were as one to her, neither pleasing nor displeasing. When, ten months later, the couple gave birth to a baby girl, she was of course, named for the Matchmaker.

After this, the Matchmaker of Hendon had no need to seek work. From Argentina and Brazil, Australia and South Africa, Israel, France, India, Portugal, Russia and Abyssinia, parents and children sought her aid. And the wider her circle of clients, the more perfect her matches became, each one more inspired than the last, until the people of Hendon began to declare that she had been given a part of the matchmaking skill which the Holy One Blessed Be He reserves for Himself.

***

“Now,” my mother said, lowering her brows and glaring darkly, “perhaps the Matchmaker became too proud and needed to be taught a lesson. Or perhaps someone else was jealous, and cast the Ayin Hara on her. The Evil Eye is real, you know, so you must always wear your red hendels, no matter what modern nonsense your mother tells you.” The children held up their left wrists, displaying the red threads tied around them. My mother nodded, satisfied. “Very good. The Matchmaker of Hendon wasn’t so clever, which might explain what happened next.”

Now the Matchmaker of Hendon’s name had become an incantation in the minds of the people. No one ever came to her single and left without their perfect mate. No one. It came to be believed that she could not fail. But when such a spell is woven, it only takes one failure for the entire vision to be destroyed. And so, upon a day, a new client came to call.

This young man had been one of the Matchmaker’s piano pupils. In fact, he brought several pieces of his own to play for her. As he began, the Matchmaker of Hendon reflected on how charming he was, his playing still shy, though much improved, his broad shoulders slightly hunched with nervousness. Yes, she thought, she would have no difficulty finding a suitable girl. She was touched by his pieces, by their simplicity, humour and gentle emotion. When he had finished playing, she told him so. Their discussion lasted several hours.

The Matchmaker of Hendon was a woman of regular and methodical habits. She worked for six days, and on the seventh she rested. From 8am to 4pm, with half an hour for lunch, she met clients and arranged matches. At 4pm, she took a walk around Hendon, to exercise her limbs, buy her groceries and, perhaps, encounter some grateful parent along the way (for modesty was not one of her primary virtues and she enjoyed receiving praise for her work). At 5pm she drank tea, very slowly, and considered the clients she had met that day. From 6 to 7 was her dinner hour. At 7pm she spread her accounts wide, and sent out her invoices. And from 8.30 to 10pm she received telephone calls informing her of the success of the meetings she had arranged. Her life went forward as rhythmically as the sweeping arm of the metronome. It was some surprise to her therefore to find, when the young man left, that her hour for walking in Hendon had already passed, as had her hour for tea. But, she reflected, if she could not interrupt her routine for an old friend, when could she?

The following day, she set to work on behalf of the young man. She selected a girl. She arranged a meeting. The meeting took place a few days later. The girl telephoned that evening: she had been enchanted, could scarcely wait for the second meeting, thought he might be the one. The young man telephoned shortly afterward. He inquired after the Matchmaker’s health, and asked whether she might be interested in looking over some new piano books. Yes yes, but the girl, what about the girl? Oh the girl had been fine enough, but not for him.

The Matchmaker frowned as she replaced the receiver. It had been over three months since she had had to arrange a second match. Her first choices were usually faultless. But no matter, she would make another attempt. That evening, as she ate her customary slice of plava cake, she found that she was drumming her fingers on the tabletop and thought that, in their rhythm, she heard the faintest sound of laughter.

The second girl would not do either. Nor would the third. Nor the fourth. It was not that they did not like him. But he appeared to be seeking something which none of them possessed. The young man became a regular visitor in the Matchmaker’s house. Together they agonised over possible choices. They played the piano while debating the qualities of a certain girl from Bratislava or another from Sao Paulo. They swapped sheet music while passing suggestions back and forth of experts they might consult. They agreed, each time, that the next choice would be perfect. But each time it was the same: the young piano player would not settle on a match.

He became notorious in Hendon. Other young people came to the Matchmaker’s door, found their allotted partner, and departed content. This boy, the people said, would reach 120 before he was satisfied with a girl. Perhaps, they murmured, all was not well with him. Perhaps his desires were not as the desires of other men. Or maybe the Matchmaker of Hendon had lost her gift. One or two young people began to seek advice from other matchmakers. One or two became six or seven, then fifteen or twenty and at last the rumours found their way to the Matchmaker’s ears.

She was shocked. This would not do, she thought. It was not orderly. Her life, which had proceeded as smoothly as a sonata, as regularly as a rondo, for so many years, had become suddenly discordant, filled with faulty fingering. She decided challenge the young man regarding his behaviour. She telephoned him that evening, at the appropriate hour. But she found the conversation rather difficult to begin; they had so many other things to discuss. At last, she blurted:

“Are you experiencing any emotional difficulties?”

The line was silent. The Matchmaker could hear the young piano player breathing, softly.

“Not as far as I’m aware,” he replied.

“Then,” she said, banging her hand on the table, “why have you not yet chosen a girl? I have found you ten and ten times ten! Are you sure you are quite well?”

The line became silent again, the young man’s breathing slow and steady. The Matchmaker looked around her quiet, tidy home, taking in the lace tablecloth and the polished brass bell on her mantelshelf. She felt suddenly afraid of what she had done.

“Perhaps,” he said, “I love someone already.”

The Matchmaker thought for a moment that her telephone was faulty. There seemed to be a ringing on the line, or in her ear. She shook the handset and said:

“Hello? Hello?”

“I’m here,” the young man said. “But I must go now. I’ll see you tomorrow. For tea.”

The next morning, the Matchmaker awoke angry. When she opened the curtains, she tugged too hard, and the pole fell to the ground. When she telephoned, she dialled seven wrong numbers in succession. In frustration, she picked at the beads on the cuff of her blouse, pulling off first one, then another, until a small shining heap was piled on the table and she realised the she had ruined the garment. She let out a cry. It was, she thought, too much. Imagine visiting a matchmaker when he was already in love! It was an insult to her profession, an insult to the girls she had found for him. Why, it was no wonder she was angry!

When she returned from her Hendon walk that afternoon, her spirits were not improved. The exercise had only increased her annoyance so that, when she approached her home and heard the unmistakeable notes of piano-playing falling from the open window, her anger ignited into fury. Even if she did leave her door open, how dare he enter her home? Play her piano? Pretend to be something he was not? She burst into her living room and began to shout. The music was stronger. The young man’s head was bowed over the piano; he simply continued to play. She saw that the piece was written in his own hand, and its notes were more than words. And as he played, she understood. And when his playing was done the room hummed, resonating where there had once been stillness.

“Whom do you love?” she asked, though she already knew.

The young man turned his head to her. And upon his face was a smile, and in his smile she read the answer to her question. And she knew that her answer was the same as his. And she began to weep.

“Children,” my mother said, “they loved each other. What joy! But what a catastrophe! Whoever heard of a matchmaker falling in love with her client? The Matchmaker of Hendon was past her middle years, but the young piano player was just a boy of twenty-two. They despaired as soon as they understood the truth, for his parents would never accept it. And without help from his parents, how were they to live? The people of Hendon would not trust a matchmaker who had married her young client. The pair tasted sweetness and bitterness in the same bite.”

My mother paused. The children grew impatient.

“What happened then, Booba? What happened then?”

My mother looked at the faces of the children. Her eyes were tender, as soft as water. She opened her mouth to speak and closed it again.

“What happened then, Booba?”

My mother smiled a strange and unexpected smile. She spoke quickly, as though trying to utter the words before she heard them.

“They were married, of course. They found that all their friends and family were far more forgiving than they’d expected. In fact, the Matchmaker became even busier than before, because now, of course, she was happily married herself. Yes, they were married for years and years and had children and grandchildren. The grandchildren were just like you except not quite so beautiful or so clever. Now, who wants rogelach?”

The children yelled and raised a forest of hands.

I stood in silence. I had not remembered the tale ending so abruptly.

***

Later, after the children were in bed, my mother and I drank tea together.

“Mummy,” I said, “how does the story really end?”

“What? What story?”

“The story you told the children, the Matchmaker of Hendon.”

My mother frowned.

“I told you how it ended. They got married and lived happily ever after. Don’t you know a good ending when you hear it?”

She took another sip of tea.

“But when you told it to me years ago, didn’t it have a different ending?”

My mother placed her cup upon its saucer.

“And what do you think that was?”

“I don’t know. Something different. More sad. More true.”

“Well.” She rubbed her brow. “I’m very tired boobelah. Another time, maybe?”

I took her hand and pressed it, inexplicably determined to hear the end.

“No,” I said, “tonight. Tell me tonight. Please.”

She made me wait until she was in bed, her lamp lit, pillows around her.

“So, my child, the Matchmaker of Hendon was in a terrible position. What could she do? If they married her career would be over, and he was in no position to support her. If she failed to find him a match, her reputation would be ruined. There was only one solution.”

“What did they do?”

“What do you think?”

I shook my head.

“They talked through the night, but all their plots and plans led back to one solution. She proposed it, in fact. He refused for seven days. Each time they spoke, she insisted it was the only course. Each time, he refused. But on the seventh day, he saw that she’d become weak with sadness and, in despair, agreed to her proposal.”

“But what did they do?”

“She found him a girl, of course. What else could they do? If they married, how would they live? He protested; he was younger and more foolish. He said they would find a way to be together, that love would find a way. She smiled and touched his cheek, but she knew in her heart that love does not make a good match. A good match needs a good matchmaker.

“So she chose a girl for him. A perfectly acceptable, pleasant young woman. And for love of the Matchmaker, he married this other girl, although until the night before his wedding he begged her to reconsider. The guests at the wedding repeated stories of the Matchmaker’s prowess, and her livelihood was saved. But you know,” my mother leaned up on her elbows, “they said that after that she lost her skill, little by little. She’d lost a sense for it, you see. Or maybe she’d betrayed whatever power it was that gave her the gift. Her matches started to fail. She would introduce dozens of couples, with no success. One or two of the matched she made ended in,” my mother lowered her voice, “divorce. Her reputation went, for all they’d tried to save it. She died broken-hearted and empty-pursed. But, though her gift failed at the end, she had made her three matches, and three times thrice three and more.” My mother laughed, a short, rattling bark. “That woman had enough merit to get all of us through the gates and into the world to come.”

“And the young piano player and his wife?”

“It took the wife,” my mother’s mouth worked, “it took her years to understand where her husband’s affections lay. And when she did, what could she do?” My mother sighed. “She had her life. She simply carried on.

“The young piano player became a piano teacher, like his beloved. He and his wife had a daughter and they lived,” my mother closed her eyes for a long moment. “They lived with a certain measure of happiness. No one can say that they did not. And the piano player who became a piano teacher grew to be an old man, and passed to his reward. But I think,” my mother placed her hand on mine, the skin paper-thin and dusted with liver spots. She squeezed my hand. “I think he always loved her. Until the day he died. And I never told him that I knew. No, I never told him.”

She turned her head toward the pillow. Within a few seconds she was asleep.

(This story was originally published in the x-24:unclassified anthology.)